A groundbreaking study from University College London (UCL) has cast new light on the complex relationship between depression and dementia, revealing that not all depressive symptoms carry the same long-term neurological risk. The research, published in The Lancet Psychiatry, identifies a cluster of just six specific depressive symptoms experienced in midlife that are strongly predictive of developing dementia more than two decades later.

The findings suggest that this small collection of emotional and cognitive complaints, rather than overall depression severity, may serve as an early warning sign of vulnerability to late-life cognitive decline.

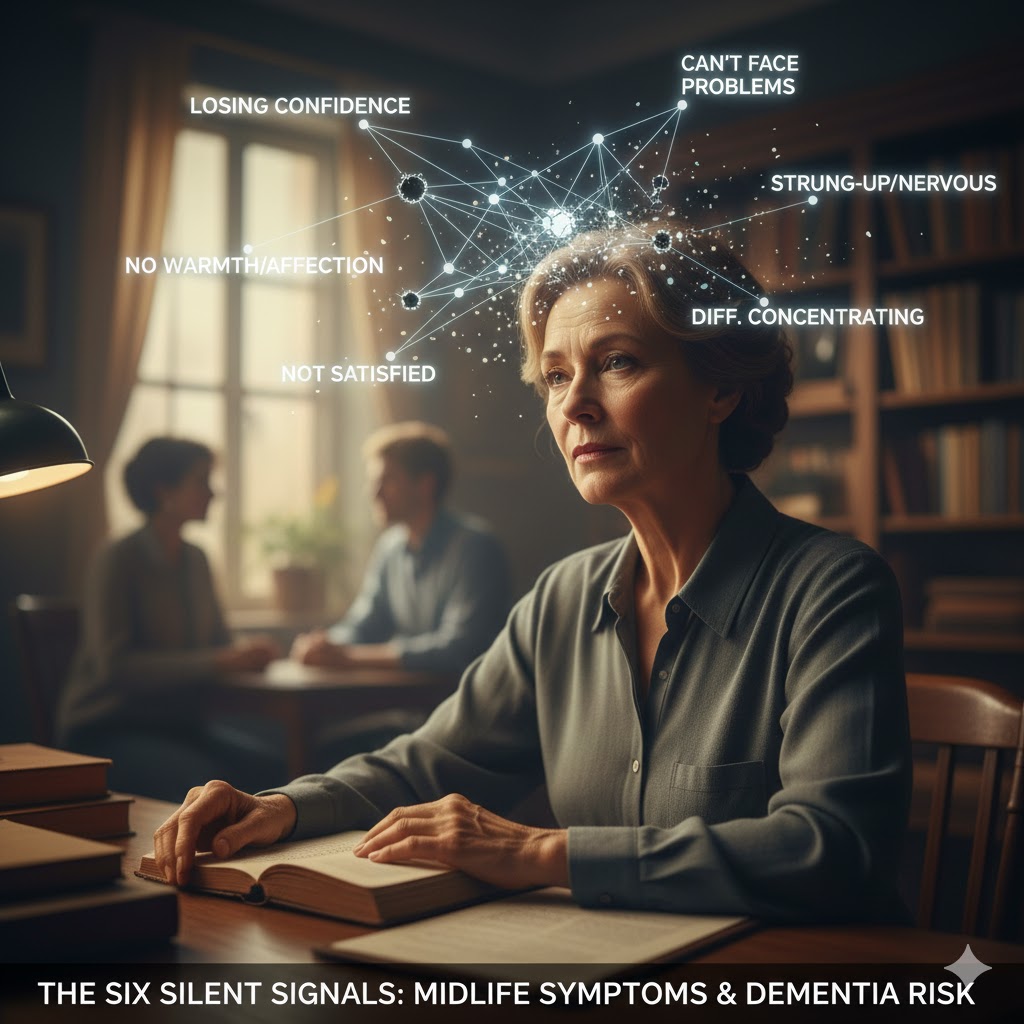

The Critical Cluster of Six

Researchers analyzed data from the long-running Whitehall II study, tracking the health status of over 5,800 middle-aged adults (ages 45–69) for up to 25 years. While midlife depression has long been established as a dementia risk factor, the UCL team’s symptom-level approach pinpointed the key indicators.

These six symptoms, when reported by participants who were dementia-free at the time of assessment, were found to drive the entire increased risk for developing dementia decades down the line:

- Losing confidence in myself

- Not able to face up to problems

- Not feeling warmth and affection for others

- Feeling nervous and strung-up all the time

- Not satisfied with the way tasks are carried out

- Difficulties concentrating

In contrast, more widely recognized depressive symptoms such as persistent low mood, suicidal thoughts, or sleep disturbances showed no meaningful long-term association with dementia risk. Notably, individuals reporting loss of self-confidence or difficulty coping with problems faced an astonishing 50% increased risk of subsequent dementia.

Erosion of Cognitive Reserve

The question is why these specific symptoms are so strongly linked to future dementia. Researchers hypothesize that the mechanism is tied to the concept of cognitive reserve—the brain’s ability to withstand damage or disease while maintaining normal function.

The six red-flag symptoms all share a common thread: they often lead to reduced social engagement and a decline in cognitively stimulating activities. Losing confidence, struggling to concentrate, and feeling emotionally detached can cause individuals to withdraw from complex hobbies, challenging work, or rich social lives. Over time, this chronic disengagement erodes the cognitive reserve that the brain needs to cope when neurodegenerative changes begin decades later.

As lead author Dr. Philipp Frank explained, this “symptom-level approach gives us a much clearer picture of who may be more vulnerable decades before dementia develops.”

Towards Personalized Mental Health Care

The study’s results offer a compelling case for a more nuanced approach to mental health screening and treatment in midlife. Instead of treating depression as a single disorder, differentiating the symptom patterns could allow clinicians to identify individuals at a higher neurological risk earlier.

This level of detail moves medicine closer to personalized treatment, suggesting that specific therapeutic interventions aimed at rebuilding self-confidence, improving emotional connection, and addressing chronic anxiety might not only alleviate depression but also serve as a preventative strategy against later-life dementia.

While researchers acknowledge the need for further studies to confirm these findings across diverse populations, the evidence is a powerful reminder that the daily emotional and mental struggles of midlife can carry long-term consequences for brain health, underscoring the vital link between psychological well-being and neurological resilience.

Leave a Reply